Scientists Examine Neurobiology of Pragmatic Reasoning

An international team including scientists from HSE University has investigated the brain's ability to comprehend hidden meanings in spoken messages. Using fMRI, the researchers found that unambiguous meanings activate brain regions involved in decision-making, whereas processing complex and ambiguous utterances engages regions responsible for analysing context and the speaker's intentions. The more complex the task, the greater the interaction between these regions, enabling the brain to decipher the meaning. The study has been published in NeuroImage.

Everyone has likely encountered a situation where the words spoken by their conversation partner did not align with their intended message. We can understand innuendos, irony, and sarcasm, even when the spoken words formally convey the opposite meaning. In cognitive science, this process is known as pragmatic reasoning—the ability to infer meaning from context, even when it is not explicitly expressed.

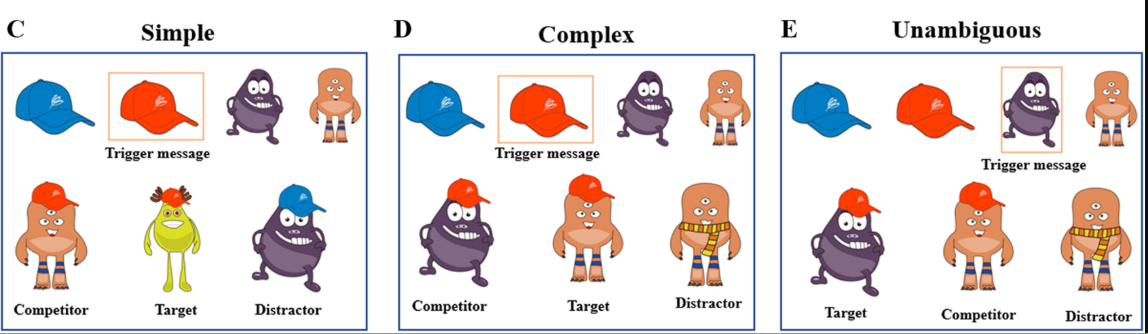

An international team of scientists conducted a study to uncover how the brain processes such situations. The study participants played a reference game, an experimental method used to investigate how people interpret ambiguous messages. In each trial, participants saw four expressible features and three monsters on the screen—a potato monster, an eggplant monster, and a pear monster. Each monster wore an accessory: a blue hat, a red hat, or a yellow scarf. The speaker sent a message highlighted by a yellow rectangle, such as 'red hat.' Participants had to determine which character was implied, but the clue was not always unambiguous, and the correct answer depended on the context. The experiment had three levels of complexity: simple, complex, and unambiguous, with the latter serving as the baseline condition. There were a total of 96 trials, with 32 trials for each level.

To identify which regions of the brain are involved in the interpretation process, the scientists recorded the participants' brain activity using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). This neuroimaging method makes it possible to study brain activity in real time. The authors of the paper also developed six computer models to characterise participants' behaviour and the strategies they use to interpret the information.

Their findings reveal that when a participant quickly understood the intended meaning of a phrase and was confident in their answer, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), involved in decision-making, and the ventral striatum (VS), associated with the feeling of having made the right choice, were active.

However, when the meaning of an utterance was ambiguous, the brain activated other regions: the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), which analyses the interlocutor's intentions and helps make sense of complex situations; the anterior insula (AI), which responds to uncertainty and tension by contributing to the generation of emotions; and the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), responsible for language processing. The more complex the task, the more actively these regions interacted, helping the brain correctly interpret the meaning.

The researchers also found that the ability to understand others' thoughts and emotions contributed to successful performance. Participants who performed better exhibited stronger functional connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and the anterior insular cortex, indicating greater flexibility in their reasoning. Previously, pragmatic reasoning was studied within the framework of general models that involve common cognitive mechanisms. However, this study reveals that interpretation strategies can differ among individuals.

'Language comprehension is not just a matter of intelligence or memory. Our brain uses a complex system that integrates language, social cognition, and context analysis,' explains Mario Martinez-Saito, Research Fellow at the HSE International Laboratory of Social Neurobiology. 'The results obtained could also have practical applications. Perhaps, thanks to such research, your voice assistant will finally be able to distinguish between sincere praise and sarcasm.'

See also:

Scientists Discover That the Brain Responds to Others’ Actions as if They Were Its Own

When we watch someone move their finger, our brain doesn’t remain passive. Research conducted by scientists from HSE University and Lausanne University Hospital shows that observing movement activates the motor cortex as if we were performing the action ourselves—while simultaneously ‘silencing’ unnecessary muscles. The findings were published in Scientific Reports.

Russian Scientists Investigate Age-Related Differences in Brain Damage Volume Following Childhood Stroke

A team of Russian scientists and clinicians, including Sofya Kulikova from HSE University in Perm, compared the extent and characteristics of brain damage in children who experienced a stroke either within the first four weeks of life or before the age of two. The researchers found that the younger the child, the more extensive the brain damage—particularly in the frontal and parietal lobes, which are responsible for movement, language, and thinking. The study, published in Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology, provides insights into how age can influence the nature and extent of brain lesions and lays the groundwork for developing personalised rehabilitation programmes for children who experience a stroke early in life.

Scientists Test Asymmetry Between Matter and Antimatter

An international team, including scientists from HSE University, has collected and analysed data from dozens of experiments on charm mixing—the process in which an unstable charm meson oscillates between its particle and antiparticle states. These oscillations were observed only four times per thousand decays, fully consistent with the predictions of the Standard Model. This indicates that no signs of new physics have yet been detected in these processes, and if unknown particles do exist, they are likely too heavy to be observed with current equipment. The paper has been published in Physical Review D.

HSE Scientists Reveal What Drives Public Trust in Science

Researchers at HSE ISSEK have analysed the level of trust in scientific knowledge in Russian society and the factors shaping attitudes and perceptions. It was found that trust in science depends more on everyday experience, social expectations, and the perceived promises of science than on objective knowledge. The article has been published in Universe of Russia.

Scientists Uncover Why Consumers Are Reluctant to Pay for Sugar-Free Products

Researchers at the HSE Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience have investigated how 'sugar-free' labelling affects consumers’ willingness to pay for such products. It was found that the label has little impact on the products’ appeal due to a trade-off between sweetness and healthiness: on the one hand, the label can deter consumers by implying an inferior taste, while on the other, it signals potential health benefits. The study findings have been published in Frontiers in Nutrition.

HSE Psycholinguists Launch Digital Tool to Spot Dyslexia in Children

Specialists from HSE University's Centre for Language and Brain have introduced LexiMetr, a new digital tool for diagnosing dyslexia in primary school students. This is the first standardised application in Russia that enables fast and reliable assessment of children’s reading skills to identify dyslexia or the risk of developing it. The application is available on the RuStore platform and runs on Android tablets.

Physicists Propose New Mechanism to Enhance Superconductivity with 'Quantum Glue'

A team of researchers, including scientists from HSE MIEM, has demonstrated that defects in a material can enhance, rather than hinder, superconductivity. This occurs through interaction between defective and cleaner regions, which creates a 'quantum glue'—a uniform component that binds distinct superconducting regions into a single network. Calculations confirm that this mechanism could aid in developing superconductors that operate at higher temperatures. The study has been published in Communications Physics.

Neural Network Trained to Predict Crises in Russian Stock Market

Economists from HSE University have developed a neural network model that can predict the onset of a short-term stock market crisis with over 83% accuracy, one day in advance. The model performs well even on complex, imbalanced data and incorporates not only economic indicators but also investor sentiment. The paper by Tamara Teplova, Maksim Fayzulin, and Aleksei Kurkin from the Centre for Financial Research and Data Analytics at the HSE Faculty of Economic Sciences has been published in Socio-Economic Planning Sciences.

Larger Groups of Students Use AI More Effectively in Learning

Researchers at the Institute of Education and the Faculty of Economic Sciences at HSE University have studied what factors determine the success of student group projects when they are completed with the help of artificial intelligence (AI). Their findings suggest that, in addition to the knowledge level of the team members, the size of the group also plays a significant role—the larger it is, the more efficient the process becomes. The study was published in Innovations in Education and Teaching International.

New Models for Studying Diseases: From Petri Dishes to Organs-on-a-Chip

Biologists from HSE University, in collaboration with researchers from the Kulakov National Medical Research Centre for Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Perinatology, have used advanced microfluidic technologies to study preeclampsia—one of the most dangerous pregnancy complications, posing serious risks to the life and health of both mother and child. In a paper published in BioChip Journal, the researchers review modern cellular models—including advanced placenta-on-a-chip technologies—that offer deeper insights into the mechanisms of the disorder and support the development of effective treatments.